Trauma & stress manifesting into emotional eating

Emotional eating is a common coping mechanism for those experiencing trauma and stress. The act of consuming food can provide temporary relief from negative emotions, serving as a distraction or source of comfort. However, this type of eating behavior can quickly spiral out of control and lead to unhealthy habits.

Traumatic events, such as accidents, abuse, loss, or natural disasters, can trigger intense emotional responses that manifest in various ways. One common response is turning to food for comfort. Similarly, chronic stress due to work, relationships, or other factors can also lead to emotional eating as a way to cope with overwhelming feelings.

The problem with using food as a coping mechanism is that it ultimately does not address the underlying issues causing the distress. Instead, it may create a cycle of temporary relief followed by feelings of guilt and shame, leading to more emotional eating. This can also lead to weight gain and potential health issues.

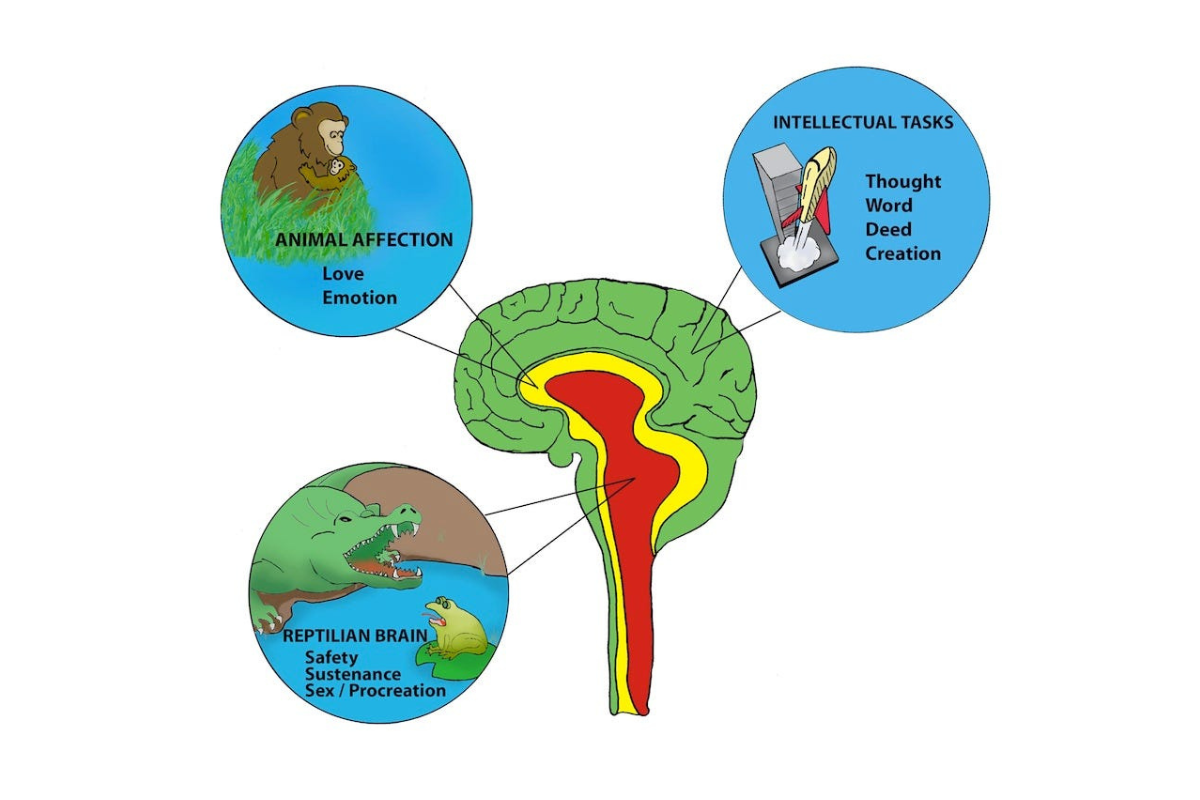

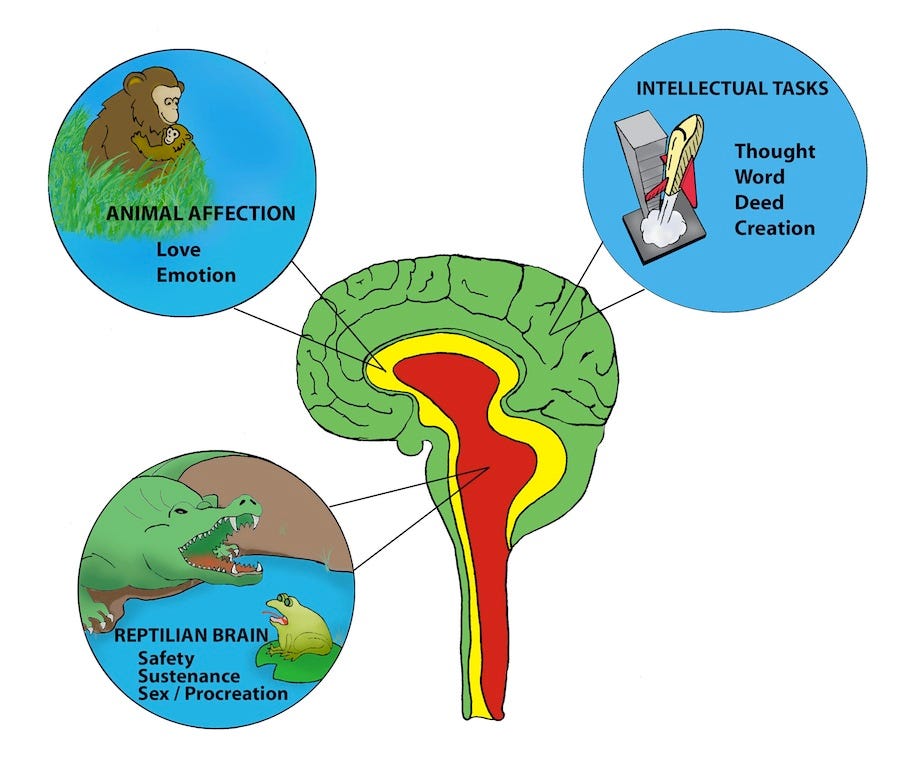

Neuroscientist Paul MacLean suggested that our brains are comprised of three parts: the reptilian brain, the mammalian brain, and the new mammalian brain (or the human brain). The reptilian brain controls our instinctual and automatic behaviors, to ensure our survival. Trauma can cause an individual's mental energy to be primarily governed by the reptilian brain, continuously placing them in a state of survival mode.

The reptilian brain manages fundamental behaviors such as eating, fighting, fleeing, and reproducing. However, the reptilian brain’s primary concern is safety and security. Until these needs are satisfied, other desires, like eating and reproducing, take a backseat.

This is evident in many of my clients who skip meals throughout the day. While they often say they simply forgot to eat, it's more likely that their hypervigilance overshadowed their basic hunger cues. They were busy concentrating on safety and security concerns like work, assisting loved ones, or running essential errands.

When we perceive a threat in our environment, we might respond more intensely than necessary because our nervous system is already on alert. As a result, our reactions can come off as too loud, anxious, or what others may perceive as overreacting.

Survival Mode

When you live in survival mode, elevated stress hormones, particularly adrenaline, make your body become somewhat numb to pain.

Consider this: Have you ever been in a high-adrenaline situation, maybe while playing a sport or during a particularly stressful event, where you banged your knee or got scratched but didn't really register the pain or injury until later that day or even days afterward?

That's the effect of an adrenaline rush. It can boost your physical strength, speed up your reactions, and dull your pain senses, making you feel momentarily invincible.

While this response to short-term stress can be impressive, when the stress is prolonged or chronic, it can detach us from our own sensations, causing us to become less aware of our emotions, thoughts, and even physical pain.

This leads to disconnection from our body, which causes compulsive behaviors. Instead of being guided by balanced emotions and rational thoughts that arise in a settled state, we're driven by an intense desire to reconnect, feel something again, and bridge the connection between the mind and body, regardless of the consequences. This was the root cause of my eating disorder.

Eating Through Echoes: When Trauma Took the Plate

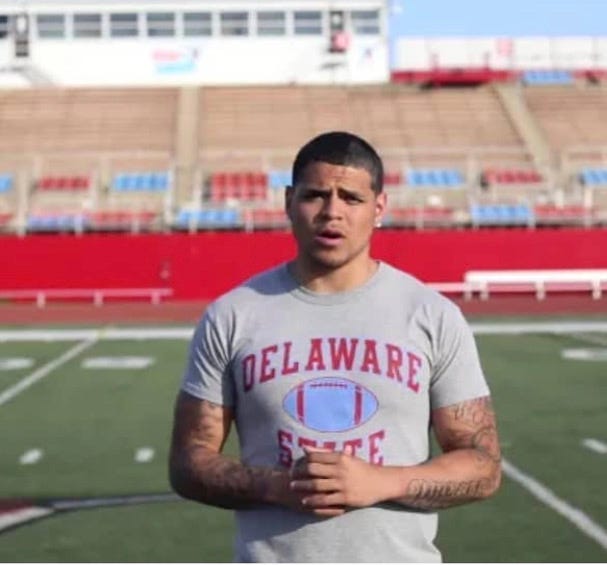

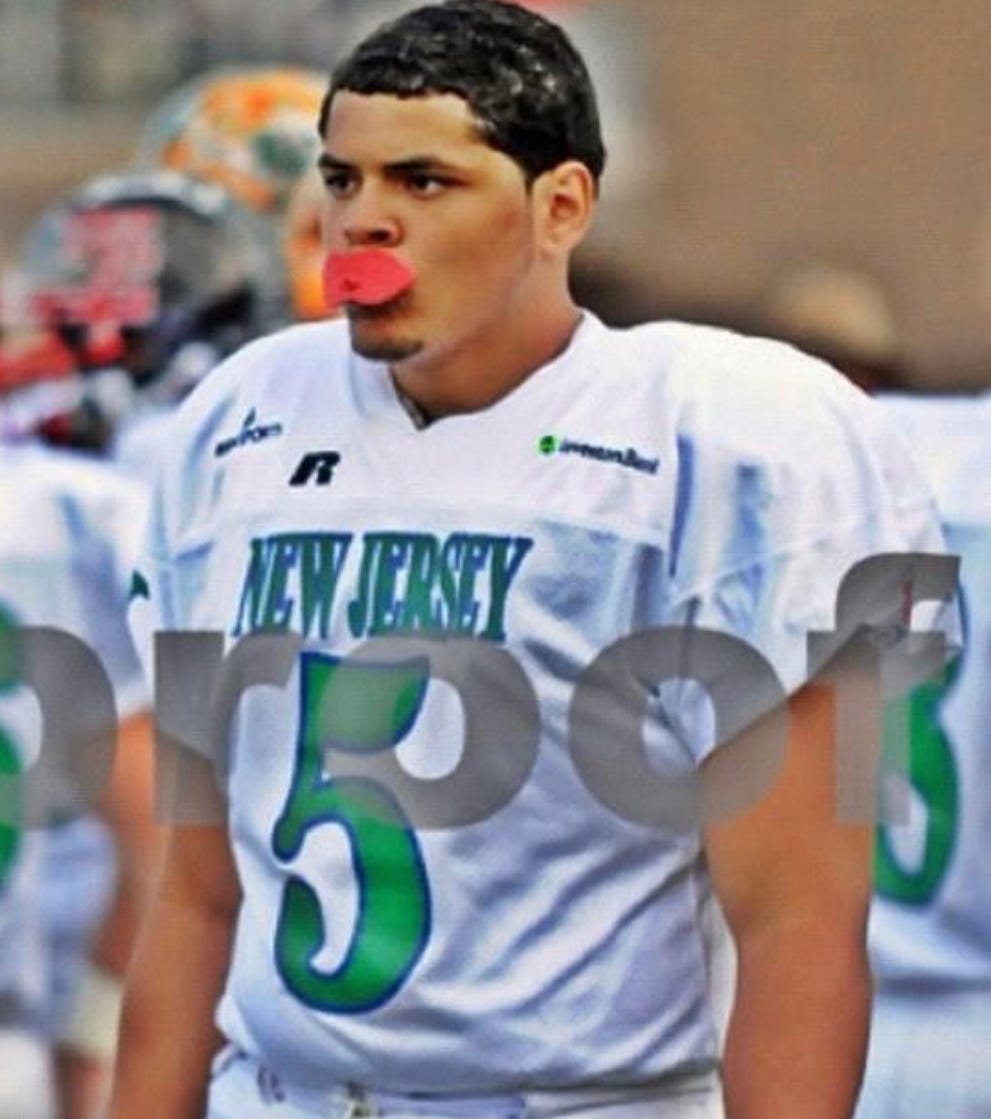

In 2012, I attended college on a full football scholarship and I left my everyday environment and family behind. When I got to college, I had a really hard time trusting people like my teammates, coaches, professors, and classmates.

I distanced myself from them. I actually found a way to get to the cafeteria, classes, and practice by walking outside of the campus, on the roads that surrounded campus, to avoid interactions with people. I isolated myself.

My ego was in charge. I was too cool to let my professors know I had learning disabilities, which led me to fail multiple classes during my freshmen year, and jeopardized my scholarship.

A couple of years earlier, during my junior year in high school, my father, brother, and I finally got our first apartment together with our own bedrooms. After years of living in the same hotel room, with my brother and I sharing a bed, we finally got a place where we were safe and had our own space. Things started to feel normal. Leaving for college two years later was one of the hardest things to do. I didn’t want the day to come.

August 3rd, 2012, I had to report to campus for football camp. I woke up that morning, grabbed my clothes, stuffed them into a laundry bag, and threw it over my shoulder. For weeks, I rehearsed how I would say goodbye to my little brother Brandon, who I was never separated from. I have four other siblings, whom I was separated from throughout my life, but my father made sure Brandon and I were never separated.

Leaving him, after protecting him for my entire life on the streets, at home with my abusive mother, and in the daily search for hotel rooms with my father, was one of the hardest things I ever had to do.

As I hugged my brother goodbye, my nervous system went into overdrive. My body grew hot, my heart raced, emotions surged, and tears threatened to spill from my eyes. I was on the verge of breaking down. But, as I always did, I clenched my jaw tightly, balled up my fists, and held my breath, suppressing the wave of sadness, and refusing to let it show. After being teased for showing such emotions as a child, I became a pro at hiding my vulnerability from the world. Besides, I'm the big brother. Showing sadness to Brandon might make him lose hope for brighter days ahead.

As I entered Dad’s room, he was asleep. I tried waking him up to say goodbye, but he was exhausted. His nights were spent planning and working for our survival, keeping us fed and safe. He had no help from my mother or any other family members. In fact it was the opposite – he had to help everyone else.

Everyone went to him for money, advice, and guidance. I was really hoping for some guidance that day. I felt lost, sad, and scared to leave. I never left Jersey City, New Jersey, and there I was, leaving for Delaware, four hours away, without Dad and Brandon. I wanted confirmation from him that everything would be okay, but I didn’t get it.

I also lost a lot of my childhood friends that summer. I had to separate myself from most of them because they were stuck with the Hood Mindset- skipping out on school to sell and do drugs and participating in gangs.

I tried my best to inspire them to do better. I became a football star, had a scholarship to attend a private high school, had good grades, didn’t do drugs, and didn’t join any gang. I tried my best to show them there was a way out. Some were inspired to get off the streets, but not all. And at eighteen years old, with a full football college scholarship, I couldn't risk my future, so I separated myself from them.

When I got to campus, I witnessed that my teammates had their family and friends drop them off, help set up their dorm, and prepare food for them for a week. Meanwhile, I was alone, with a laundry bag of clothes over my shoulder, staring at them. I wished my family was there to drop me off and help me set up my dorm.

Growing up with family in and out of jail, I heard endless stories of how isolated jail is, how you are surrounded by cement walls, with strangers and no loved ones. I knew my situation was very different than jail, but I couldn’t help but feel that I was, indeed, in jail, in my dorm room with cement walls, surrounded by strangers, with no loved ones, and feeling alone.

I had mastered the streets of Jersey City. I’d created routes to avoid gangs, saving myself and Brandon from being jumped, robbed, or even killed. When I got to campus, I immediately created routes to avoid people, even if it took an extra twenty minutes.

A few weeks after leaving for college, Brandon called to inform me that they were being evicted. I panicked and started making plans to go home. My problem was that I had football, and as a Division One athlete, my schedule was completely busy. Still…I found a way.

After our games on Saturdays, we got to rest until Monday morning, so I made my way back to Jersey after games. I drive for four hours, feeling beat up from a week of football and cramped in my little car. All I could think about was how to help my father and brother as much as I could.

I made this trip every weekend and during this time my mother's situation got worse. She was hospitalized for overdosing and arrested a few times. As her behavior got worse, she was sent to the psych ward, which I would visit during my four-hour trip. It was very difficult to see my family struggle so much. I felt guilty for leaving them and going back to a dorm that had electricity, heat, hot water, and a meal card that allowed me to eat three times a day. This made me hate college.

When I got back to college, I looked forward to the day being over so I could return to my dorm and eat the cookies I’d stuffed in my pocket every day from the cafeteria. I would put on one of the TV shows that Brandon and I watched when we were younger. Comedy was our favorite. With all the stress, loneliness, and learning disabilities, college was difficult for me and all I wanted to do at the end of a hard day was to go back to my room, eat sweets and laugh.

When I went back home for winter break after my first semester, my family commented on how much weight I had gained. I tried my best not to let this hurt my feelings, but it did. I was always the fat boy.

Before going to college, I’d finally lost some of that weight, just to end up with it back on after one semester. So I started to diet. I ate one tilapia a day with an orange, then fasted for twenty-four hours. Within a few months, I lost sixty pounds.

The hardest part was not binge eating at night, so I came up with a solution. I gave myself one big cheat day a week. Anytime those cravings came up at night, I manipulated my mind to look forward to Friday night, when I would have a pizza from Dominos and brownies.

When Friday finally arrived, I had a whole routine. I set the dorm room up, my favorite TV show, the portable table next to the bed, and a bottle of laxatives on the dresser. After eating the pizza and brownies, I would follow it up by drinking the whole bottle of laxative.

I made Friday my cheat night because I knew most of the guys in the building I shared the bathroom with on my side of the hall were out partying. I had that bathroom all to myself, which allowed me to clear out all the food I just ate. This cycle went on for a good two years, and it is one of my biggest secrets.

Writing this is the first time I have ever shared this with the world. I didn’t know this was an eating disorder, nor did anyone around me mention it. I also didn't realize I had a sensitive nervous system.

Even with all the trauma from my past, combined with my current stress, I did everything possible to appear and feel normal. I was striving to rise above poverty and past trauma, all while wrestling with my subconscious mind.

I found myself echoing the feelings of my childhood - confused, lost, and pained. Only now, I was a young adult, distanced from home, and facing real-world consequences. And then, one day, as if guided by fate, I stumbled upon a man named Paul Chek on YouTube.

“When the student is ready, the teacher will appear”

After finishing my second year of college, and barely achieving the grades I needed to retain my scholarship, I headed back home for the summer. I had been away for a year, with only my 16-hour weekend visits, and I thought things might have changed in my hometown. But as I looked around, I realized the streets were the same as always and my family and friends were caught in the same old cycles.

On hot summer days, with no air conditioning and sweat dripping down my face and onto my phone, I spent my time watching YouTube videos of Paul Chek, who many call “the Godfather of health and fitness.”

Paul Chek founded the CHEK Institute, which teaches a holistic approach to health, fitness, and well-being. I had never seen anyone connect the mind and body like he did, not even my college professors. But Chek taught beyond just the mind and body. He explained how our thoughts, past, and environment have a deep impact on our well-being. That's when I started to see the connections between my issues and my past.

When I got back to campus for my junior year, I knew I needed to seek help. Fortunately, my scholarship provided me with an athletic counselor. I felt it was time to face my trauma and vulnerabilities head-on. I remember having a counselor in middle school who helped, but as I grew older, I became more guarded and private about my struggles.

Visiting home that summer though, reminded of my challenging past and the reality of life without direction. I understood I had a chance to change things. I knew running from my problems or trying to handle them on my own wasn't the solution anymore.

I was sent to a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with PTSD, an eating disorder, and ADHD. I informed my professors about my learning disorders, and they all supported me. My grades improved, the binge eating stopped, and I started to spend time with my teammates.

My coach told me to stand up in one of our football meetings. He complimented me for my improvements in the classroom and on the field. He then asked me to give some words of inspiration to the team. My words were something they didn’t expect.

“If you have trauma and are struggling with mental health problems, stop being too cool and get help.” The room became silent as I sat back down.

After the long silence, my coach said, “If you have trauma and were either diagnosed with a mental health disorder or believe you have mental health problems, stand up.”

Fifty-four of the eighty football players in the room stood up. Looking at those who stood up, I realized most came from urban areas, like I did. I wasn't the only one trying their best to leave the hood, suck up the pain that trauma had left me, and put on a front that everything was okay.

Eventually, they all got help and most stopped me on campus when they saw me alone and thanked me for my bravery. They all shared how it had changed their lives.

This was the moment I realized the power of being honest and vulnerable. Not only did I help myself, but I helped others.

I thought, “If I helped a few of my teammates with my honesty, imagine how many other people would find inspiration from my story and my approach for healing.” I was inspired to do more digging.

The more I learned about how connected the mind, body, and emotions were however, the more of an outcast I became in my classes. I spent four-and-a-half years at Delaware State University getting my Bachelor of Science in Movement Science, which covered nutrition, strength and conditioning, and physical therapy. I learned a lot in college, but I encountered problems whenever I asked the professors questions.

For example, I didn't believe calories in vs. out should be the primary focus for weight loss, especially for those with hormonal imbalances. Yes, the principle of calories in vs. calories out is vital for weight loss. But what triggers someone to feel so hungry and exhausted that they overeat and lack the energy to exercise? My professors didn't see eye-to-eye with me on this and it became a frequent roadblock and disagreement. I wondered if I was ahead of my time.

Identify the underlying cause, not just the symptoms

In my eight years as a coach, working with thousands of clients, I've realized a pivotal truth: lasting transformation isn't possible without recognizing the power of the subconscious mind and having a strong enough purpose to drive change.

This is particularly true for emotional eating.

My own journey with emotional eating began with the realization that I was suppressing my emotions—energy in motion. A visit home during a summer break showed me that nothing had changed there, which reignited my purpose to overcome generational trauma and poverty. I saw that emotional eating was hindering, not helping, my legacy.

If you find yourself struggling with emotional eating, or if you weren’t even aware that you were doing it, consider the following steps:

- Seek Help: Don’t let pride stand in your way. You’re not alone in this struggle.

- Identify the Moment: Pay attention to when you start to eat emotionally. I call this the Sublime Moment—the instant you become consciously aware of a subconscious habit.

- Reflect and Respond: When you catch yourself in the act, pause and reflect on what triggered you. What emotions are you trying to feed? Once you identify the trigger, work on creating a new ritual to express these emotions in a healthier way. For me, it was developing what I call the High Vibe Walk, which was instrumental in overcoming my emotional eating.

The High Vibe Walk

The High Vibe Walk is a 45 to 60-minute stroll that can be taken around your neighborhood. If your neighborhood is in an environment that stimulates your nervous system too much, you can do your High Vibe Walk in a peaceful park close to your home. If the weather is not favorable for an outdoor walk, you can enjoy your High Vibe Walk on a treadmill. This will ensure that you stay on track with your exercise goals regardless of the conditions outside.

During your walk, reflect on someone who has achieved success in your desired field or pursuit of purpose. Listen to their podcasts, audiobooks, or interviews, and start educating yourself. Learn from the trials and errors of their journey as you walk, and absorb the lessons they've learned.

When emotions peak, it can be challenging to control negative thoughts and stay present. The High Vibe Walk engages your body to actively express energy in motion and leads to a calmer mind. This activity provides the perfect setting for grounding you in your self-image and fuels your motivation to evolve into your new self—The You You Never Knew.

Implementing mindful breathing during the High Vibe Walk serves as another essential tool. By inhaling through your nose and exhaling through your mouth, you engage your parasympathetic nervous system and calm your Sensitive Nervous System. This is also known as the rest and digest system, (the opposite of the fight or flight system).

This practice mirrors the benefits of meditation, and offers a dynamic form of mindfulness for those who struggle with traditional sitting meditations.

My clients and online community contact me daily to share their experiences with the High Vibe Walk. They express how it has significantly helped them feel grounded and manage their stress. This practice has been instrumental in improving their mental, physical, and emotional health. And now, it’s a tool for you to use to help you on your journey to overcoming overeating.

If you’ve found that overeating has been a significant barrier in your weight loss journey, I suggest incorporating the High Vibe Walk into your routine. This practice has not only helped me personally but has also been a turning point for many of my clients. It’s a proactive step to counter emotional eating by channeling your energy in a positive and healthy way.

For those of you who are new here, I’ve put together a series of essays that delve into the connections between trauma, hormonal imbalances, and their impacts on fatigue and weight gain. These writings also include nutritious meal ideas and motivational insights to support you on your path to wellness. Here are a few essays that could be particularly beneficial:

- The Unseen Cycle of Weight Loss

- Keeping Weight Loss Simple

- Easy Meal Plan For Weight Loss, Digestion, and Energy

Let's keep being GREAT!

BegreatWithNate